History of Paper Beads

Making paper beads is a traditional craft that goes back, in England at least, as far as the Victorian age. Young ladies would gather socially in their dining rooms, whilst making beads from scraps of wallpaper rolled on knitting needles. They would then polish the beads with bees wax and string them on to long pieces of yarn. They would then be used to make door curtains to divide rooms.

This practice was then revived in the 1920s and 30s for jewellery making.

More recently paper beads have been made in cooperatives as part of development projects in countries such as Uganda. This sees a move away from charitable aid towards business enterprises that provide sustainable income and development opportunities. The techniques used remains largely the same as used in Victorian times, but with recycled paper from printing companies and recycling markets, rather than wallpaper samples.

Paper beads are also made by independent bead making artists around the world and sold through their own web sites or online market places such as Etsy and Artfire.

Requirements

- Paper – Magazine pages, wrapping paper, wallpaper, and coloured art paper, or more specialist papers such as handmade Japanese Washi or Chiyogami paper.

- Pencil – for marking up the paper.

- Ruler – for measuring up.

- Craft Knife, Rotary Cutter or Scissors – for cutting out. If you are using scissors you should use the longest pair available so as to reduce the number of cuts required along each length.

- Straight Edge – for cutting against.

- Self Healing Cutting Mat – for cutting on.

- Metal Skewer or Thin Wooden Dowel – for rolling paper against. Commercially made bead rollers are also available.

- Soft Paint Brush – for applying glue to the paper.

- Glue – for securing your rolled beads. Undiluted PVA is perfect but there are many other alternatives.

- Wooden Cocktail Sticks – for holding your rolled beads when drying or when varnishing.

- Soft Paint Brush – for applying varnish. A quality brush is preferable at this point as it is less likely to leave bristles on the surface of your beads.

- Varnish – for waterproofing your rolled beads. Quick drying marine varnish is perfect and is usually touch dry within 1 hour and ready for a second coat in 4 hours. Experiment with gloss, satin, matt, and antique finishes.

- Oasis Florist Block, Polystyrene Block, or similar – for securing the beads whilst varnishing and drying. Push a cocktail stick holding an individual bead securely into the block.

- Place your paper face down on your work surface so that the side facing you is not the side that will form the outside of the bead

- At intervals apply another line of glue to secure your work so far. This is far cleaner than covering the whole triangle in glue at the outset.

- When the paper is completely rolled make sure the end is securely stuck down before rolling the bead through your fingers with a light pressure to ensure it is cylindrical and secure.

- Slide the bead from the skewer or dowel and transfer it to a cocktail stick and set to one side in your florists block or polystyrene block to completely dry.

Refinements to this Technique

- When you have a good number of beads prepared you should then brush each bead with a few coats of varnish to make them water resistant. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions, but ensure that when touch dry you rotate them on the cocktail stick so they don’t stick when fully dry. Several thin coats give a much more polished result than one thick coat.

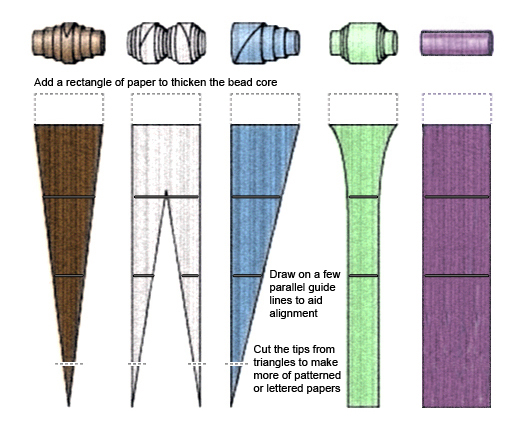

- To provide a neater finish to your bead and to show more of the paper, simply cut the tip from the triangle as indicated in the diagram above. This will give a broader end to the last part of the roll. This is particularly effective if you are using patterned paper or paper with text, as it will show the detail of the pattern or lettering.

- To provide a stronger, neater, flatter core to the finished bead add a rectangle of paper to the long base of the triangle as shown in the diagram above. This doesn’t need to be more than 1.5cm long, and should simply allow for a few turns of the paper around the skewer or dowel. It also makes initial alignment of the paper easier. It has the added bonus of making the beads sit better against each other when strung. On the downside, the initial stage of laying out the paper for cutting becomes more involved, but in the end it is worth the extra effort.

- To monitor progress and to ensure ongoing symmetry it is worth while adding some parallel pencilled lines to the back of the paper at the marking up stage.

- Once you have a set of finished beads experiment with finishes and embellishments to add extra interest – be it gilding, wire wrapping, adding fancy papers, using specialist glazes, or simply painting them, the options are endless.

Paper Sources

The main criterion for selecting paper comes down to weight. If the paper is too flimsy it is likely to tear whilst it is being rolled and if it is too heavy it will prove difficult to roll resulting in a loose and uneven bead. The only other issue is likely to be with finish. Before settling on a particular paper check that it will stick to itself with the glue that you are using and that any applied colour or print will not run when glue or vanish is applied to it. Otherwise, as you will see from the few examples provided below, the options are endless.

Art Paper

Art Paper

A trip to a local art supplier will present you with a rainbow of artists’ papers all neatly stacked in a display cabinet and available by the sheet! Used for pastels, charcoals and pencil drawings most of these papers are also the perfect weight for paper beads. In addition to the range of colours many of these papers are also finely textured or grained, which will add a little something extra to the resulting bead. A name to look out for is Fabriano Tiziano. When compared with wrapping paper this is a far cheaper solution albeit minus the patterns.

Copy Paper

This paper is perfect for making solid colored beads. It comes in a wealth of different colours and because it is designed to go through a printer or copier it is the ideal paper to use with a template image. With a little work on a graphics package on a computer you can set up a template document, which will print out cut lines on each sheet, removing any need to measure prior to cutting! Another positive is that it is always likely to be in stock should you want to do a re-run of a particular set of beads in the future.

Specialist Paper

For that really special bead, or a paper bead embellishment, there is nothing finer than using a specialist paper be it Japanese Chiyogami, Italian Fiorentine, or French marbled. These are the preserve of fine paper and book binding suppliers.

Junk Mail

These largely unwanted additions to newspapers and letters can be used in much the same way as magazines. A better end for them than the bin!

Magazine Pages

This is a great way to recycle old magazines and the resulting colour combinations achievable are endless. When selecting pages remember it is the edges of the strips that will be visible on the finished bead as well as the end of the roll. Unless you are using paper from the large format magazine, typically fashion related titles, it may be worthwhile opening the staples on the magazine and using a double page spread.

Newspaper Pages

The weight and composition of newspaper means it is best used for tapered beads. On the plus side most modern newspapers use colour fast inks but it is worth checking how it works with the glue and varnish that you will be using. A second benefit of newspapers is the width of the sheets particularly if you make use of the Sunday broadsheets.

Paper Shopping Bags

Whether plain or printed this paper makes for really good beads. Plain brown paper provides a wood-like appearance when varnished, which can be enhanced by selecting antique effect varnishes. Printed brown paper bags tend to have pleasant earthy tones, which again give a vintage feel to the resulting beads.

Parcel Paper

Like the plain brown paper bags this paper gives a lovely wood-like finish once varnished and is a nice weight to work with. Plus there are more colour options available than previously.

Wrapping Paper

Wrapping paper is an ideal medium simply because of the breadth of colours and patterns available. However the heavier better quality papers can be expensive and unfortunately it is these that are less likely to tear when damped or lose print when handled.

Warning:

Having been varnished paper beads will survive a rain shower but they don’t like to go swimming or to do the washing up!

Pin It

Paper beading is highly addictive!